Category menu

Research study explains the brain basis for feeling tired after tic suppression

Posted on 18 January 2021 by Pippa McClounan

Find out how researchers at the University of Sussex used brain scanning to look at brain activity in people with tics.

Many people with TS can temporarily suppress or withhold their tics, if they want to – such as in social situations.

However, a lot of people with TS report that this is a really tiring process that takes a lot out of them. Researchers at the University of Sussex have used brain scanning (functional magnetic resonance imaging) to look at brain activity in people with tics and control participants without tics, while participants chose to release or to withhold actions.

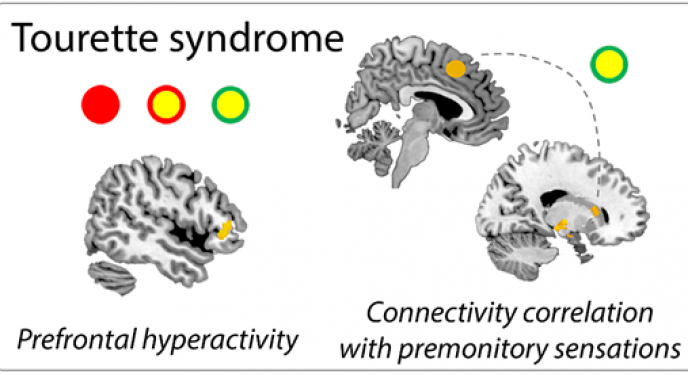

This enabled the researchers to investigate the brain processes by which people suppress actions, and compare these between the TS participants, and the control group. The researchers found a region of the prefrontal cortex, called the inferior frontal gyrus, was more active in the TS participants when they were choosing to withhold an action. This brain area is known to be important for inhibitory control – stopping yourself from performing a movement. As well as this heightened prefrontal cortex activity, another region of the brain further down the ‘motor command chain’, the primary motor cortex – which is responsible for releasing movements including tics – was slightly overactive in TS.

Researcher Charlotte Rae, who led the study, said: “These exciting new results explain why people with TS report feeling tired after suppressing tics for a long time – because their prefrontal cortex has to work much harder to withhold movement than in those of us without tics. We think that their prefrontal cortex is having to work so hard in order to compensate for their primary motor cortex being so keen to get movement out of the brain and into the muscles. This is in contrast to the controls, who don’t have a hyperactive primary motor cortex, and so their inhibitory control region in the prefrontal cortex doesn’t have to put in so much effort, in terms of activity levels, to stop actions being performed”.

The researchers factored in the fact that patients were sometimes ticcing during the scanning to their analyses.

Charlotte said: “To get a clear measure of inhibitory control that we could compare to controls who don’t tic, we asked participants to carry out a specific task, in which they could choose whether they wanted to press a button, or choose not to press and to withhold. This is something that both control and TS participants can do, whereas only people with TS can tic, and can choose to suppress tics! To make sure that we got a pure measure of inhibitory control in both groups, we didn’t ask TS participants to suppress their tics during scanning. That meant some patients did show the occasional tic. We factored this in to our analysis by video monitoring participants, then adding ‘tic timelines’ to our statistical models. That gives us the confidence the results we are seeing are not due to patients expressing or suppressing tics during the brain scanning alongside the inhibition task”.

The researchers also found some interesting results when TS participants chose to press the button, instead of inhibiting. When TS participants chose to press, connectivity between the pre-supplementary motor area – which plans actions – and the basal ganglia, which lets those action plans out to the spinal cord – was correlated with the patients’ premonitory sensations. That is, those patients who report having worse premonitory urge sensations before tics – like something is ‘itchy’ or that you just ‘have to let it out’ – showed greater cross-talk between these movement areas. This suggests that these aspects of motor circuitry in the brain might be hyperconnected in people with worse premonitory sensations, explaining why they feel such strong urges to move.

Professor Hugo Critchley, senior researcher on the study, said: “We are always tremendously grateful for the involvement of individuals who volunteer to help such research. We need to continue to unpack complex brain processes for better understanding to improve the lives of people living with Tourette syndrome”.

The research team would like to thank every participant who took part, especially TS participants for whom brain scanning can be hard work, and Tourettes Action for helping to advertise the study to participants.

You can read the full report here

Rae CL, Parkinson J, Betka S, Gould van Praag CD, Bouyagoub S, Polyanska L, Larsson DEO, Harrison NA, Garfinkel SN, Critchley HD. (2020) Brain Communications